AN ADMISSION OF BIAS

PHS students discuss affirmative action policies within the college admissions process

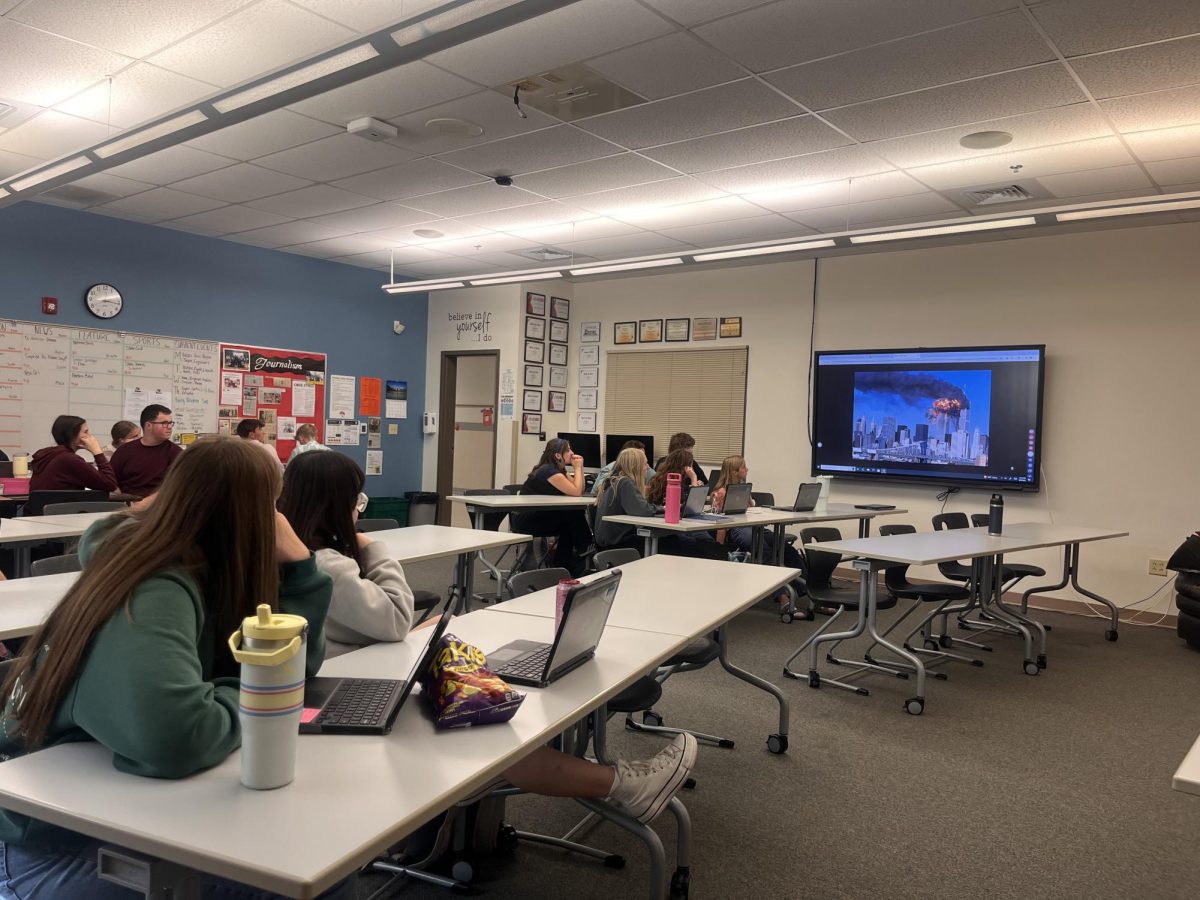

Photo Courtesy of Nathan Feller

Senior Austin Graft surrounds himself with scholarships and college admission information in hopes of discovering a scholarship with standards as low as his self esteem.

Much like nearly everything in the United States today, the collegiate world conformed to pressure to make accommodations for minorities in order to avoid accusations of misogyny, bigotry and racism.

These affirmative action programs apply to all post secondary institutions across the States.

According to a Q&A page from the American Civil Liberties Union, “Race conscious policies, such as affirmative action, aim to address racial discrimination by… responding to the structural barriers that have denied underrepresented students access to higher education.”

While a policy that attempts to ensure minorities an equal opportunity during the admissions process by providing exclusive benefits may seem like an easy fix, some students at PHS feel that affirmative action is unfair and irrelevant.

“I don’t think [affirmative action policies] are appropriate,” senior Jacob Orr said. “I don’t think it should matter… school is a place for academics, so [admissions] should just be purely based off of your academic standing or your financial needs.”

The entire purpose of the affirmative action policies is to try and eliminate racial bias within the college admissions process and create equal opportunities for all genders and ethnicities.

However, rather than eliminating racial and gender bias, these affirmative action policies are, in part, responsible for the creation of diversity quotas within collegiate institutions.

“I feel like [gender and racial quotas] just complicate things more,” senior Armando Hernandez said. “I don’t see the big deal. I feel like they should base [admissions] off just academic skill and capability instead of their gender or race.”

Diversity quotas are essentially an attempt to increase the percentage of one of more minority groups within a specific position.

Although it was ruled unconstitutional to base admission solely off race after the Regents of University of California v. Brakke case in 1978, the case also ruled that race could still be considered under the condition that it is one of many factors.

“I just don’t understand why [diversity] should even matter,” Orr said. “[Schools] just end up excluding people that actually want to go to their school, so they can meet a quota just to make the school look better.”

Unfortunately, the Regents of University of California v. Brakke case did not rule the consideration of race in the admission process completely unconstitutional, so colleges and universities are still legally able to consider race and gender during the admissions process and when creating scholarships.

“[As] an immigrant, it’s going to be harder for me to try and find any benefits.” Hernandez said. “So I’m perfectly fine with [racially exclusive] scholarships, especially if they benefit me.”

The 1978 ruling has led to the existence of scholarships with specific, intangible qualifications such as the Arnita Young Boswell Scholarship which only allows female African-American applicants, or the ACS Scholars Program which only accepts African American, Hispanic, Pacific Islander or American Indian applicants.

“I would say that it’s a good thing for some people,” junior Kiyoko Hayano said. “Sometimes they might have some things to fight against, whether it’s a home situation or it’s a [financial problem].”

There’s no doubt that these types of scholarships are beneficial for many collegiate students who belong to minority groups.

However, the affirmative action policies have not truly addressed racial inequality. These policies have merely excluded people of Caucasian ethnicity from any sort of scholarships specifically designed for them.

Providing special opportunities and scholarships for all other ethnicities except for Caucasians is not correcting racial discrimination but promoting it.

Instead, perhaps collegiate institutions should consider removing racial preference altogether.

“[Academics and financials] should be the only two things that schools should care about,” Orr said.